We are Shuai Gu and Ariana de Souza, from the Cassar Lab of the Earth and Climate Sciences Department at Duke University. We joined the BLOOFINZ cruise in order to collect biological nitrogen fixation data in this eastern Indian Ocean region, where no field measurements have been available so far, limiting our understanding of how nitrogen fixation is distributed in the world oceans. We are using a breakthrough method our lab created, known as the Flow-through Acetylene Reduction Assays by Cavity Ring Down Laser Absorption Spectroscopy (FARACAS).

N2 gas is a huge nitrogen reservoir which makes up 78% of the air that we breathe, but it is not biologically accessible to most organisms just like us human beings. Nitrogen fixation is a process in which microbial organisms can take atmospheric nitrogen and cook it up into something that they can use in their bodies. Only a few microbes can perform this life-creating task – the select few are known as diazotrophs. Not only is the fixed nitrogen useful for diazotrophs themselves, other organisms like planktons can utilize it for their growth as well (and they might feed the baby tuna all the way through food web!). Thus, nitrogen fixation is crucial to provide bioavailable nitrogen in the oceans, especially in oligotrophic waters where nutrient concentrations are extremely low in the surface (for example, the region we were during this cruise). Because nitrogen is directly related to organism growth and biomass, we often look at how the nitrogen cycle and the carbon cycle interact with each other. This interaction has important implications in light of climate change, for example fertilizing the oligotrophic oceans through nitrogen fixation contributes to sequestering CO2 from the atmosphere into the sea.

We need information on nitrogen fixation in order to better understand the oceans and climate change, but many of the methods out there to measure nitrogen fixation only offer very few data points at a time because of the work and time needed for each discrete measurement. Because of the FARACAS method, we can measure nitrogen fixation at much higher resolution continuously (getting more data points from one single cruise than that you can find from all literatures in the past!) and significantly improve knowledge in the field!

The way our method works is as follows: we first need a clean tube that can go into the surface water of the ocean. It should gently pump seawater along with all the organisms into a lab on the ship, without injuring those diazotrophs or contaminating the water! We were able to achieve this due to the incredible work of Dr. Peter Morton and Dr. Thomas Kelly. Once the seawater is in the lab, we mix it with a chemical (acetylene) that the diazotrophs are known to react with. If the diazotrophs are fixing nitrogen, they’ll be making the enzyme needed for this reaction, known as nitrogenase, which also like to reduce acetylene! This enzyme latches on to acetylene and changes it into a gas known as ethylene. Once we mix the seawater with the acetylene, we give the diazotrophs a little time to swim around in an incubator, recover from their startling journey, sunbathe in our LED wrap, and hopefully work their nitrogenase magic, and then we measure how much ethylene gas is present in the water. That way we can measure the rate of ethylene production, and convert it to nitrogen fixation using a known conversion factor (and calibrating this factor with discrete 15N2 nitrogen fixation incubations).

Figure 1: The tubing towed on a BOOM in the surface ocean, which collects the seawater continuously for the FARACAS measurement, under sunset in the Indian Ocean on R/V Roger Revelle.

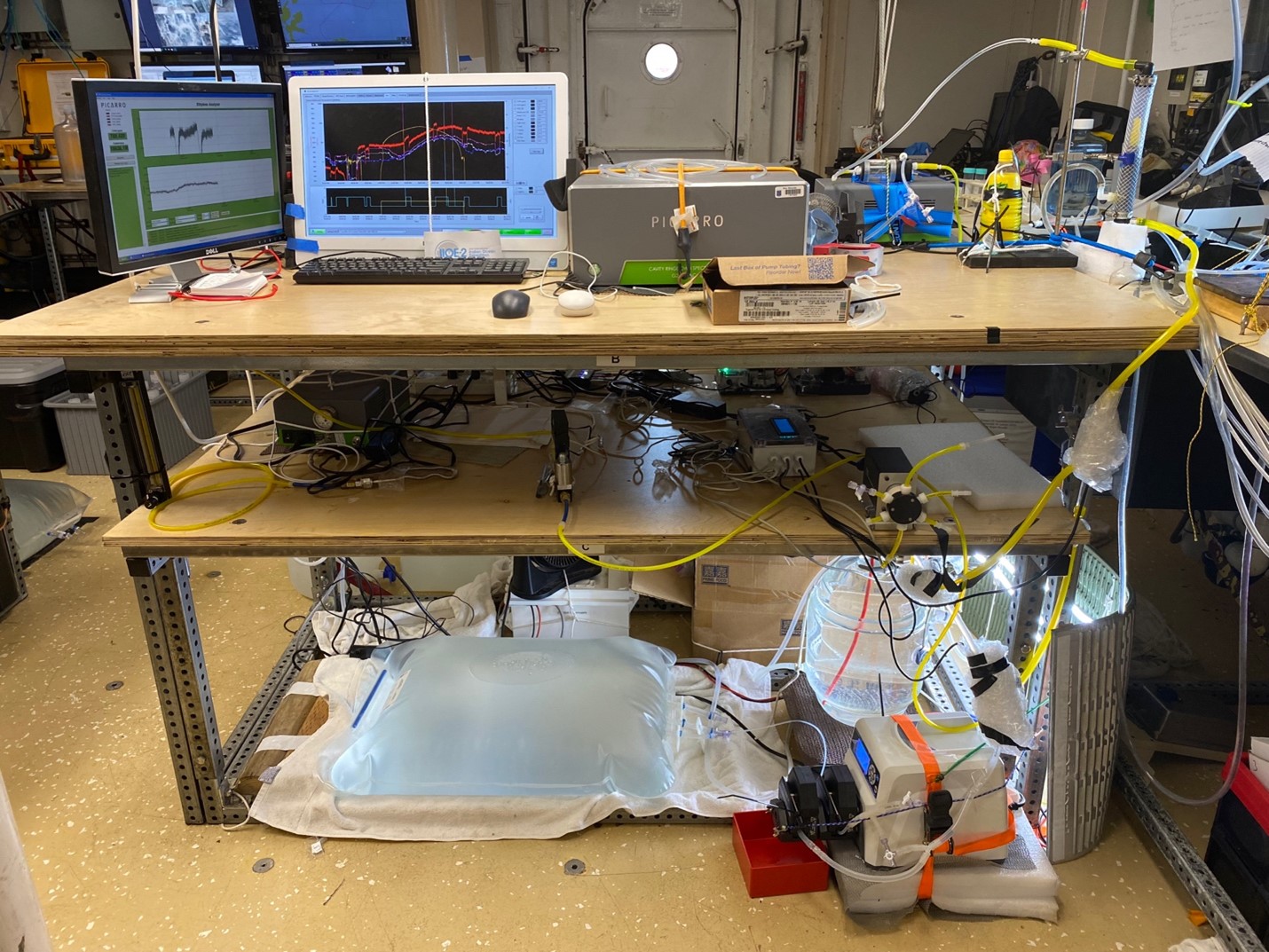

Figure 2: FARACAS setup in the Hydro Lab of the Roger Revelle. Filtered seawater is filled by acetylene gas in the water pillow at bottom left. This tracer water is then mixed with fresh seawater from outside the ship, and pumped into the glass incubator (bottom right). We estimate nitrogen fixation rates by measuring how much ethylene has been produced after the water stays in the glass incubator for approximately 90 minutes, using the grey box instrument on top of the bench.

The setup looks like a lot, and that’s because it is. We are constantly checking on parts of the instrument, and making sure that there are no leaks or valves switching the wrong way or water shooting into places it shouldn’t be (which is hard when you’re in the middle of the ocean). This instrument requires 24/7 maintenance, and two eyeballs watching it at all times. We switch off times so that we can sleep, and that way one of us is always able to be in the lab.

Here is a little more about each of our experiences during the cruise!

Ariana de Souza (she/her/hers)

I am currently a second year PhD student in the Cassar Lab at Duke University! I’m from San Jose, California, and I got my bachelors degree in Biology at the University of California, Los Angeles. This was my first cruise. I’ve had many of my cruises canceled or postponed because of the pandemic, so I was terrified that this one would be too. The leadup to the cruise was really tense – every few days we thought we wouldn’t be able to go, because the plans kept changing or Shuai and I weren’t sure our materials would arrive in time. I developed a toxic relationship with the UPS over winter holidays and would call them desperately multiple times a day for shipping udpates. But soon, we realized that the cruise was a go, that we wouldn’t have to cancel our flight tickets to Guam, and the terror set in! I was going to be on a cruise ship! I was going to have to work constantly for two months! I would have to give up TikTok, and risk returning two months later completely ignorant of all trends!

Quarantining in Guam was quite an experience. It was incredibly stressful as we got notice that members of our party had contracted covid, and we waited each day to see if we would be next. In-between working on proposals and studying the FARACAS for the cruise, I kept my spirits up by obsessing over what to eat each night for dinner, sitting on my balcony trying to use the Force to get other people to leave the hotel swimming pool so I could swim safely in isolation, and watching as much Netflix as was humanly possible before our 2 month cruise. And very very luckily, Shuai and I both were negative and were able to board the cruise! We set up the FARACAS in the Hydro Lab of the Roger Revelle, and spent the next few days troubleshooting the instrument and soaking in each sunset that we could before our lives revolved around the FARACAS.

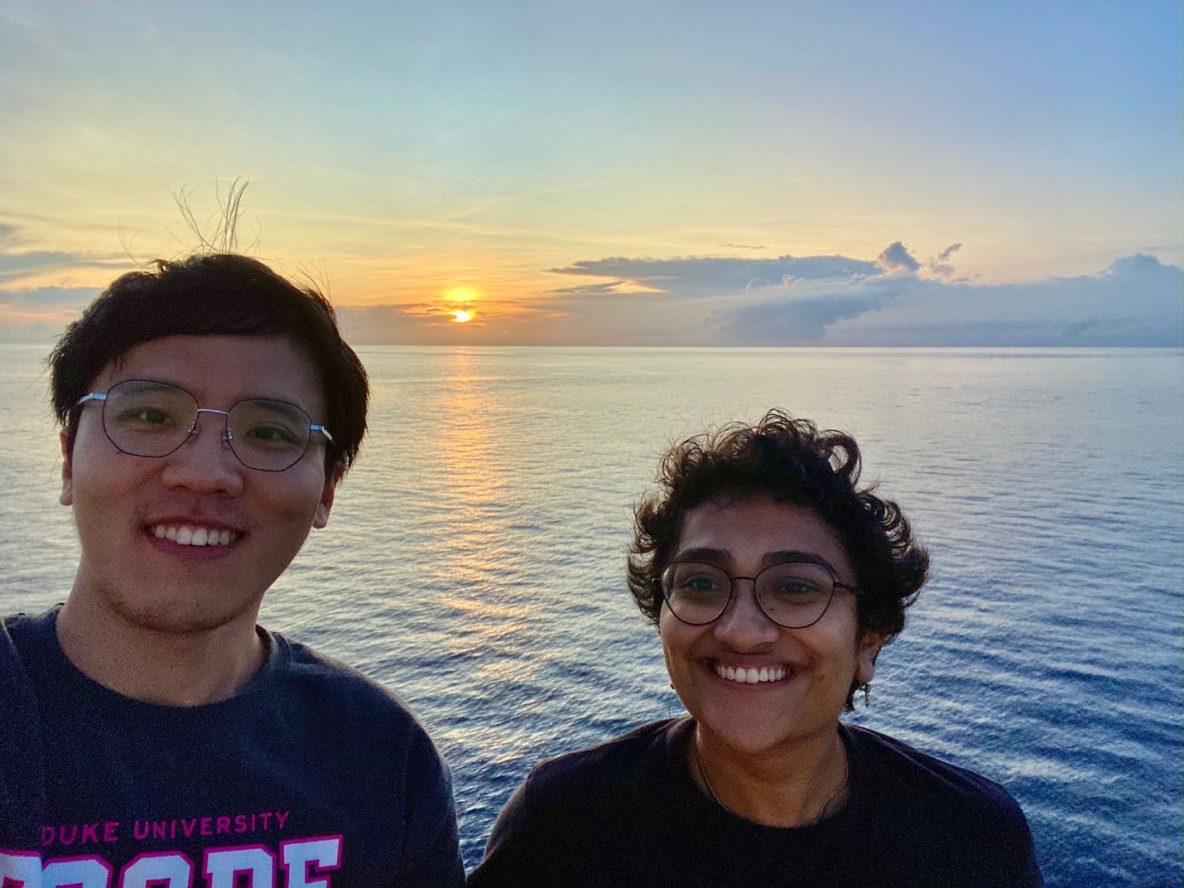

Figure 3: Ariana and Shuai crossing the equator in Indonesian waters.

I worked from 7:30 AM (breakfast)– 11:30 PM (lunch), and then from 5:30 PM (dinner)-1:30 AM. While in the lab, I read a total of around 80 books. I would like to dedicate this part of the blog to the creators of the app Libby, who allowed me to devour book after book on my phone. Working on a ship constantly showed me how important the people are to the attitude of a ship. We were surrounded by the same people for two months, and it would have been a nightmare if they weren’t all so incredibly nice and funny. They were all extremely supportive, and every day I realized how important it was that science was composed of wonderful, collaborative, and genuinely passionate and interested people.

This experience was my first on a ship, and I think it was a really positive one. Though it was a tremendous amount of work, and I can’t wait to sleep for more than 7 hours at a time when I get back on land, it was so rewarding. Performing field work has always been an interest of mine, and this was one of the most amazing experiences in my time as a scientist. I’m so excited for my future cruises in my time as a PhD student, and the incredible places they’ll take me.

Shuai Gu

After finishing my bachelor’s and master’s studies in marine chemistry at Xiamen University, China, I joined the Cassar lab at Duke University as a PhD student studying marine nitrogen fixation. Under all the uncertainties caused by the pandemic, I am so happy to travel for a cruise again and finally get onboard the R/V Roger Revelle on an island where I never expected myself to be. It’s always been exciting to explore this world, including the science world covered by water that we don’t understand enough.

Working at sea was filled by unexpected troubles and sleepless nights, which I wouldn’t have survived without the desserts from all meals, the espresso from Pete, and all the snacks I brought from the other side of the earth. The BLOOFINZ cruise marks my 200th day in the field, with more than four months at sea where I have always enjoyed the sunsets and sunrises. It also marks the 5th continent that oceanography has taken me to, and I hope to visit all seven in the near future.